Seeing Stars:

Andromeda, The Tempest and Mything Shakespeare

In Shakespeare and the Goddess of Complete Being, Hughes points to Shakespeare’s interest in Occult Neoplatonism as the basis for the philological construction of his dramatic landscapes. According to him, Shakespeare’s spiritual interests draw on a hugely diverse catalog of mythologies, and those mythologies are then contained in and signified through the appearance of sacred images, flashes of discourse that suggest the narratives, the archetypes, and essentially, the tropes through which Shakespeare colors his plays and helps us navigate his created universes. Though Hughes identifies Shakespeare’s treatment of both “Venus and Adonis” and “Lucrece” as the bedrock of his “consuming myth”, these basic “images”, the divine goddess and her consort, lend themselves to other similar mythic patterns that may fit some of the environmental conditions of each drama more specifically. In yet another fractal of what Hughes defines in Shakespeare and the Goddess of Complete Being as the “tragic equation”, Shakespeare uses Perseus’ marriage to Andromeda as part of the mythic backdrop through which we can interpret The Tempest.

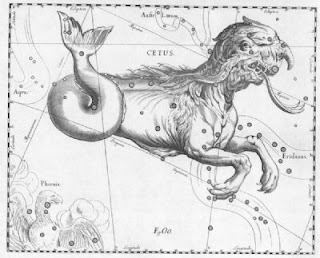

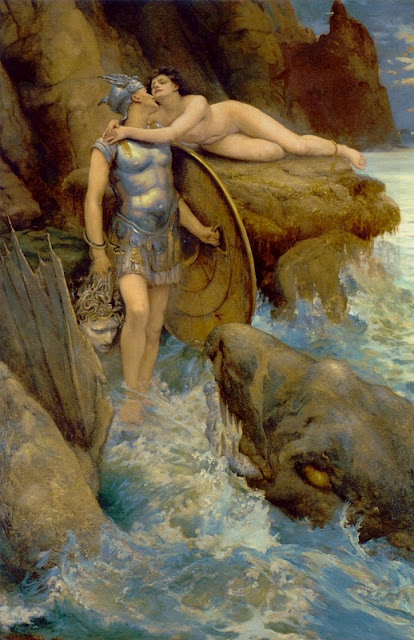

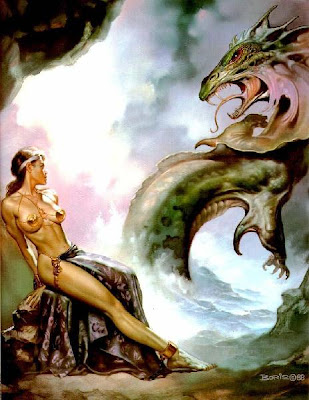

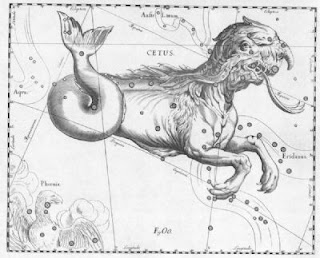

Shakespeare’s indisputable knowledge of mythology in general, and that of Greek/Roman origin in particular, would suggest his familiarity with Ovid’s Andromeda. The story occurs in the beginning of many of Ovid’s passages devoted to the heroism of Perseus, the famed conqueror of the Gorgon. The scene between he and Andromeda begins as he is soaring over Ethiopia on his winged sandals and spies the beautiful maiden chained to the rock by the sea, a sacrifice to be devoured by the terrible sea monster Cetus in payment for her mother’s hubris, and in hopes of providing some relief for the Ethiopians that have since been punished on land and sea. After inquiring with the Andromeda as to her situation, Perseus agrees to rescue her just as Cetus is rising out of the surf. The hero slays the monster, frees Andromeda, and takes the maiden as his bride, all to the great satisfaction of her grateful and repentant parents. (Ovid, 103)

The Tempest opens in much the same way. The boiling sea, the “tempestuous noise of thunder and lightening”(I.i) reminds us of the violent surf beating against the rocks that Andromeda is bound to, an image of human vulnerability juxtaposed against the terrible forces of nature. Yet, while the imagery remains relatively congruent, the perspective in The Tempest suggests the same kind of tinkering that Shakespeare demonstrated in his treatment of “Venus and Adonis”. Rather than the hero spying the maiden from afar and coming to her rescue, the roles are reversed, and scene two opens with Miranda the maiden entreating her father to “allay” the “wild waters”, that she has “suffered with those that [she] saw suffer.” (I.ii, 1-5) Here Miranda, not her would-be rescuer Ferdinand, is the onlooker, the sympathizer, watching as he and the others are nearly consumed by the sea.

Though she is no longer bound to helplessly to the rocks, in The Tempest, Miranda is not entirely freed from her bondage; she is herself the goddess chained to the island. Her isolation feeds her longing for companionship, sexual or otherwise, which Ferdinand fulfills more by accident then by a demonstration of heroism. Rather than the valiant, monster-slaying hero of classic Greek myth, here Ferdinand is the victim; he is shipwrecked, mediocre-looking, a prince “by circumstance” rather than merit. Musing on his daughter’s “choice” in suitors, Prospero reminds her that in regards to men in general, “[Ferdinand] is a Caliban,/And they to him are angels.” (I.ii, 480-482) Miranda, of course has no means for comparison, confessing to Ferdinand that, “I would not wish/Any companion in the world but you;/Nor can imagination form a shape,/Besides yourself, to like of.” (III.ii, 54-57) Compared to her father and Caliban, Ferdinand, though no hero, makes a fine suitor in respect to her available options. Again, Shakespeare, as in his “Venus and Adonis”, has rendered the goddess’ consort into something of a disappointment. While Ferdinand does not outwardly reject Miranda, he remains undeserving of her affections to begin with.

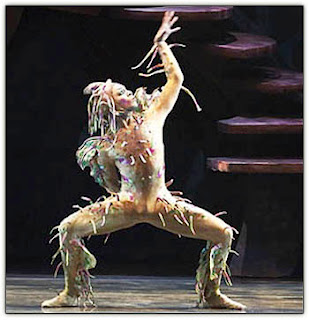

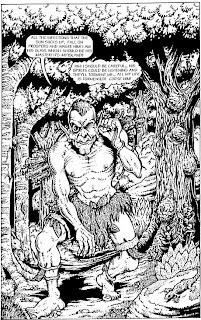

Miranda is unable to see her self and others in the context of greater humanity. Her motherless upbringing no doubt limits her ability to express herself as a female being. “I do not know/ One of my sex/ no woman’s face remember (III. ii, 48-49) she says. Miranda has no reference for which to help her reach her goddess potential. Sycorax, the only female element which she might have had example of, was in fact slain by her very own father. The play makes no other mention of a potential maternal figure for Miranda, creating a void that Prospero can occupy simultaneously with his paternal function. In this way, Prospero strives to fulfill all the various roles in Miranda’s life as needed. In a sense, it is Prospero who is Miranda’s promised hero. It is he who kills the hell queen, just as Perseus had slain the Gorgon. Prospero, then, is both the goddess destroyer and the surrogate mother-goddess, but this manipulation of roles most clearly aligns with Andromeda’s predicament in the following way: When, in the beginning of Act Four, Prospero warns Ferdinand, “Do not smile at me that I boast [Miranda] off”(IV.i, 8-10) he alludes to Cassiopeia’s same blunder, bragging about the unsurpassed the beauty of his daughter, the very trespass which landed Andromeda on the rocks as sacrifice for her mother’s hubris. Ferdinand’s reply resonates with the myth as well, he answers, “I do believe it/Against an oracle”, perhaps referencing Ammon’s decree that no relief would be given to the Ethiopians until Andromeda was exposed to the sea monster. Miranda’s exposure to the sea monster is, of course, not quite the same as the Andromeda’s, her experience with Caliban is yet another demonstration of Shakespeare’s alteration of myth for his own purposes. Here, Caliban is hardly the terrible sea monster that Cetus is. He is not feared by the King of the Island, but rather enslaved by him. While his features remain quite disgusting, he has in essence begun his evolutionary transformation from the terrible Greek legend toward an amphibious and relatively civilized creature who dwells on land, and to the surprise of Trinculo and Stephano, speaks English. Caliban, on one hand, is like Miranda: isolated, without a mother, and looking for companionship. Evoking pity in the audience, he describes his first encounter with Prospero: “when thou cam’st first,/ Thou strok’st me and made much of me…and then I loved thee,/ and showed thee all the qualities o’ th’ isle.” (I.ii, 333-338) Caliban, like many of Shakespeare’s characters, embodies almost contradictory personality traits. Despite his pitiable circumstances, however, he also retains many of the less redeemable qualities identified with the Cetus, his earlier form. Prospero’s initial warmth towards Caliban, for example, is quickly extinguished when he “seek [s] to violate the honor of [his] child”, to which Caliban boasts that, had he not prevented him, he would “had peopled else/ This isle with Calibans.”

It is in this way that Caliban is a secularized version of Cetus, and this complication of Cetus’ unprovoked rage lends Caliban a particular authenticity because there is a human motivation behind his wrath. The argument between Trinculo and Stephano pertaining to the nature of Caliban speaks to this dualism: they refer to Caliban as “a dunken monster”, “a ridiculous monster” a “lost monster.” Thus, Caliban can be seen both as the physical embodiment of the mythic “sea monster” image, or as merely acting out those mythic qualities in a certain way. On one hand, he is a friendly, singing monster and, on another, a monstrous slave, the boar sent from the queen of hell, plotting to brutally “brain” his master.

Like Caliban, many of the characters in The Tempest are emerging from their original mythic contexts, liberating themselves from the rage, the entrapment, and the limitations of their original forms. Yet, for Prospero there seems to be some uneasiness in regards to this transformation. When Ariel asks for his emancipation, Prospero scolds him, saying, “Dost thou forget/ From what a torment I did free thee? [. . .] Once in a month recount what thou hast been,/ Which thou forget’st.” (I.ii, 250-251 and 263-264) In a similar moment, he addresses Miranda’s ignorance of her own mythic character; he describes her as, “my dear one, thee my daughter, who/ art ignorant of what thou art”(I.ii, 18) and urges her to seek her origin in the “dark, backward and abysm of time.” As both a creator and a player in The Tempest, Prospero’s remark about Antonio’s treachery begs the same question, “my trust/ Like a good parent, did beget of him/ a falsehood in its contrary as great/ as my trust was” (I.ii 93-97) Without divine intervention, the people of the island have strayed far from their mythic origins.

Even Prospero, who appears to be obsessed with time and origin, himself eventually forgets his obligations. The bridal feast attended by Love and Hymen is a moment that occurs in both Andromeda and The Tempest, and it is here that because of Prospero’s failure to remember his mythic origins, that the sea monster, the enraged boar, the revolting slave, enters with a “strange, hollow, and confused noise”; the very picture of Cetus rising out of the boiling sea, the mythic reality waiting for all of us just below the surface, just as their constellations circle silently overhead..

Works Cited

Hughes, Ted. Shakespeare and the Goddess of Complete Being. New York: Farrar Straus Giroux, 1992. Print.

Ovid, and Rolfe Humphries. Metamorphoses. Bloomington: Indiana Univ. Pr., 1972. Print.

Shakespeare, William, and Alfred Harbage. Complete Pelican Shakespeare. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1981. Print.